Caught With His Trousers Down: The Ira Robbins Interview

By Steven Ward (May 2001)

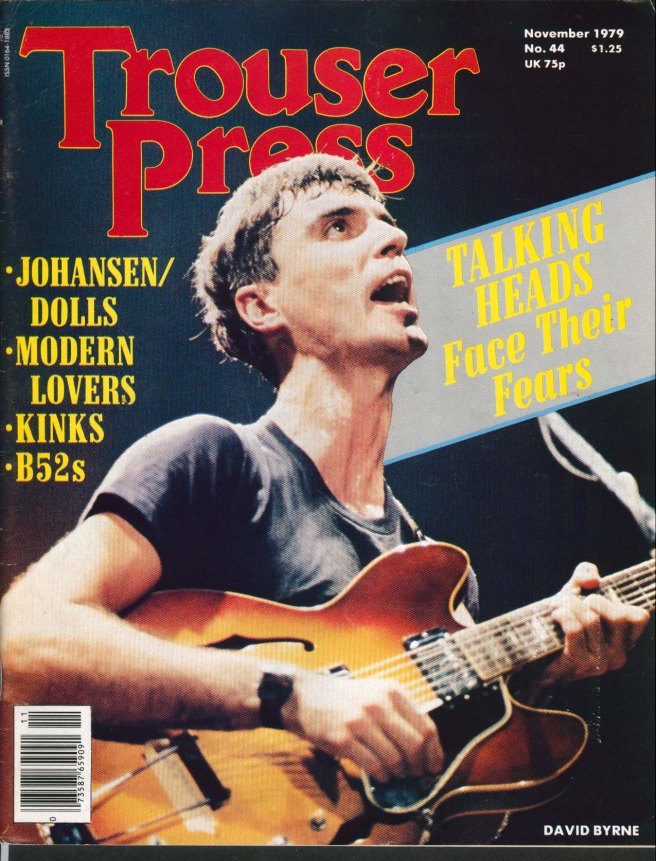

If anyone out there has a million dollars and wants to start a music magazine, please let Ira Robbins know about it. Robbins, the co-founder and co-editor of Trouser Press, has said that a million dollars would be the only way anyone could talk him into running a music magazine again. It’s not that he wasn’t any good at it — in fact, Trouser Press quickly grew from a stapled fanzine with a devoted cult following to a glossy monthly magazine that was as good or better than competitors Rolling Stone and Musician at certain times in their publishing histories. For 10 years, from 1974 to 1984, Trouser Press worked towards becoming the “alternative” magazine of its day — a precursor to the early Spin, back when that magazine was any good.

In the mid-’70s, Robbins, the late Karen Rose, and co-founder Dave Schulps started Trans-Oceanic Trouser Press to start championing English music which the conventional rock press was ignoring. Trouser Press writers and editors went to work, telling the world about the Who, King Crimson and Roxy Music. They did not worship at the feet of ’70s critical darling, Bruce Springsteen. (Robbins said he was never a fan.)

When the magazine folded under financial and cultural pressure (MTV had just started and it was forcefully taking over the Trouser Press niche), Robbins continued his crusade with a series ofTrouser Press record guides. Now into its fifth edition, Robbins’s books have become the standard alternative music guides for music fans and rock writers.

Today, Robbins works in syndicated radio and freelances for Mojo, Salon.com, and other publications.

In the following e-mail interview, Robbins talks about the history of Trouser Press, his favorite rock mags and writers, the problem of being pigeonholed as an “alternative” music critic, and the possible future of Trouser Press on-line.

Steven: Trouser Press was a rock fanzine you started with Dave Schulps in 1974. The fanzine quickly turned into a professionally done and well-respected rock magazine that was forced to close almost 10 years later in 1984 because of financial pressure. Do you miss putting out a monthly music magazine and do you think you would ever get involved in something like that again?

Ira: Actually, finance was only one of the factors that contributed to my decision to end Trouser Press in 1984. The music world had changed, music media had changed, the lives of the staff had changed, our audience had changed–all of which conspired to make the original thrill of having a credible forum to do with as we saw fit feel more like a Sisyphean duty to fill up a bunch of damnably empty pages every month.

The emotional rewards, for me at least, had dissipated in the face of MTV’s ability to make new wave bands come alive, with audio and video, in a way we couldn’t match on paper. Part of why we existed was because commercial American radio completely ignored the bands we cared about, and college radio was only beginning to matter in the new world.

MTV, in its early-’80s infancy, lunged for the colorful (read: new wave) and the video-savvy (that meant English, since the U.K. use of video to promote bands on TV was already established, albeit not in such a concentrated way) acts–Adam Ant, Duran Duran, Stray Cats (Americans who had started their career in London), Culture Club, the Cure, Depeche Mode, et al. That wasn’t all we did, but they stepped on our toes a lot.

I was frustrated at our fiscal insecurity and, turning 30 after 10 years of doing Trouser Press and nothing else, I discovered that real life, adult life, couldn’t be postponed indefinitely. Plus there was only so much rejection of the mainstream possible if staying in business was a goal. We unintentionally had a new audience–teenyboppers excited by our coverage of their faves but too young to share our sensibilities and our skepticism: one cover story on Duran Duran that attacked the band’s flaws caused howling letters of disillusionment and anger from kids who just wanted the good news on how cute they were. How could we put them on the cover and not worship them? It made sense to us–a big story is a big story, and a band is a mix of good and bad. Little did we know that no one else thought that way. These days, what serious publication dares think that way?

Which brings me to the question you actually asked–do I miss it? Sure. It was fun to publish completely independent music reportage and criticism. Trouser Press stood for things. Our readers thought of us as a friend with strong opinions. We clearly favored cool bands over old-hat stooges, but we had a real respect for veterans and their complex careers. We (I) loved Cheap Trick, the Who, Roy Wood, Sparks, Todd Rundgren and the Clash. We (I) hated Bruce Springsteen and all the manly Americans who bellowed rather than sang. We thought Patti Smith might be over-rated, and we couldn’t cope with L.A.’s hardcore punk (a generational failure, no doubt). But we had a huge soft spot for the enigmatic charmers in the Residents.

It was all seat-of-the-pants, idiosyncratic, irreverent self-indulgence, but it was wonderful fun. It sucked getting dicked around by record companies, advertisers, distributors and all the rest. I took it all personally–I can vividly recall arriving full of enthusiasm and optimism to our 13th floor office on 5th Avenue on many occasions only to discover that the morning’s mail contained a few bucks in checks on days when the rent, or payroll, or a $20,000 printing bill was due. It wasn’t just the money, really, it was the feeling of powerlessness, that the enterprise we put so much of our lives into could so easily be derailed by another company’s incompetence or bankruptcy, or the record industry suspicion that print advertising wasn’t of any real use to them. It was a tough and lonely battle, externally and internally, and we didn’t learn until it was over how many people we were important to.

Having started out so small and informal, we never grew into a well-run organization–although we got our work done and seemed on top of things, how we did it was always pretty slapdash. When I look back at the old issues, they look and read better to me than I remember them from the creative side. It was that kind of experience–hard to watch the food being prepared but tasty once it got on the table.

So, yeah, there are parts of it I miss. But after it was over I was able to regain friendships that were seriously challenged by working together, and that means a lot to me to this day. I look back and see how well Spin did after we quit–not that the two are in any way connected, but if we’d had some of their money and a bit of encouragement, maybe we could have become a much bigger deal than we ever were. When I decided I’d had enough, I looked around for a buyer, had an accounting firm groom us for a sale, and there were no takers.

I’m glad to have done Trouser Press and glad not to be doing it anymore. Sometimes you have to know when to leave what you’ve done frozen in time and let others carry on. Fortunately, the Trouser Press books–which we started doing in 1983, while the magazine was still up and running–provided 15 added years of continuity for me, the magazine’s name and its ethos.

Would I do it again? I’ve always said if someone wanted to put up a million bucks, providing the business acumen and leave me alone to be the editor, I’d love to run another music magazine. Our slow but steady approach to business was fine in some ways, but a lack of initial capital was ultimately fatal, dooming us to be a small-time operation even when we might have done a lot more. I was never a businessman, and we were never able to get past print-it-they-will-read idealism. Successful magazine publishing, I discovered, involves a lot more than a good editorial “product”–it needs a marketing push, professional salespeople, distribution expertise, muscle, resources and management discipline–none of which we ever had. Oh well.

Steven: For those who don’t know, Trouser Press was started because you wanted to cover bands that mainstream rock mags were ignoring. That turned out to be a lot of British rock and progressive rock bands in the mid-70s. As time went on, non-mainstream acts turned into the punk/new wave/alternative wing. During the magazine’s last few years, did you consider yourself or the magazine a champion of “alternative” bands or just scribes who were chronicling the bands that were non-mainstream?

Ira: It’s nice of you to use the verb “champion,” since that is exactly the reason why we put out the magazine. At the outset, our view of what mainstream rock magazines were overlooking included history as well as obscurity, so we latched onto the past (namely British Invasion bands) as well as pub rock, prog-rock and assorted marginal artists few publications cared about. But we were hardly doctrinaire about it. (As you may recall, both Genesis and King Crimson were considered prog bands at the time.) In the first two years (12 issues) of what was initially known as Trans-Oceanic Trouser Press, we covered the Who, Mott the Hoople, Todd Rundgren, Peter Frampton, Steve Harley, Marc Bolan, Brian Eno, the Rolling Stones, Status Quo and Roxy Music–among others.

Confession: As the mid-70s wore on, we found ourselves covering bands we knew we were supposed to care about but actually didn’t (privately, we referred to them, using a bit of borrowed British slang, as “wallies”). I was opposed to making too much of the New York underground scene we all loved and took part in, because we didn’t want to be seen as locally obsessed. It wasn’t as if bands like Blondie or Television or Talking Heads would ever escape the Bowery (as I foolishly believed) and be able to be heard by anyone outside the metropolitan New York area. (Bear in mind that most CBGB/Max’s groups never released any independent records, and major labels were very slow to come calling. Then came the deluge, and in retrospect we quickly found out how naïve that view had been.)

Flash forward to the early ’80s. New wave had become new romantic; the class of ’77 was either dead or digging itself into a rut of decreasing quality and originality. The pop stars we could stomach–Adam Ant, Go-Gos, Culture Club, Cyndi Lauper, Madness, Squeeze, Stray Cats–were just that, pop stars, which made them less emotionally rewarding to champion. U2, R.E.M., Blondie and others were numerically significant AND good, but there weren’t enough of them for a monthly. So, yes, in a sense we were phoning it some of the time, and that hypocrisy really made us lose enthusiasm for the whole enterprise. Meanwhile, we were somewhat removed from the indie rock stuff that was exciting–the Dead Kennedys, Neighborhoods, X and Pere Ubu were cool by us, but Black Flag was really not appealing to me musically in 1982. They sounded like the era we’d just come out of, minus the insight and credibility. (OK, so I was wrong about that, too.)

Steven: For better or worse, when I think of a rock critic who specializes in new wave or alternative music, I automatically think of Ira Robbins. Do you think you have been unfairly tagged with that title or do you think the connection is an apt one?

Ira: Unfair but hardly unwarranted. My musical interests, taste and areas of expertise, I’m happy to say, extend further than A Flock of Seagulls to the Butthole Surfers, but I suppose we all have to be typecast for something, so I can’t really complain. (And I did title the first Trouser Press book a “guide to new wave records,” so who am I to quibble?)

Long before there were skinny-tie bands, I was devoted as a fan and journalist to the Who. (When I handed Pete Townshend a copy of Trans-Oceanic Trouser Press #3, the second issue of ours to feature his band on the cover, in 1974, he took it to be a Who fanzine rather than a generalist rock magazine.) I’ve cared about Bob Dylan, blues, soul, folk music and British rock of the ’60s my whole sentient life–one of my best recent CD purchases was an old Canned Heat live album I had worn out on vinyl. Glam/glitter is also a favorite era of mine (Roxy Music/Slade/T. Rex), and I also love old-school hip-hop, Blossom Dearie, bluegrass, smart singer-songwriters and Humble Pie.

I would hate for people to assume, based on my writing and editing work, that I woke up in the mid-’70s, decided the Vapors were the bomb and never gave it another thought. By the time Elvis, the Pistols, Clash, Stranglers, Vibrators, Damned, Buzzcocks, Pere Ubu, Devo, etc. crossed my radar, I’d been a professional music journalist for five years and a devoted rock and roll fanatic for 15. And I’ve kept involved, active and enthusiastic to this day. I’ve co-produced a J. Geils compilation, written liner notes for Yardbirds reissues and the Electric Light Orchestra box set, reviewed the Broadsides collection and done a lot of other things regarding music–all because I wanted to.

Steven: Tell me about your favorite rock magazines in the early ’70s. What were you reading before you started Trouser Press and what rock critics were your favorites? Which ones influenced you?

Ira: I have trouble recollecting exactly what I was reading in those days, but I can tell you with some surety that future Dictator Scott Kempner turned me on to Creem in high school, and I found that very inspiring. I was desperate to write for it, and sent them a couple of pitch letters/spec submissions which elicited encouraging scrawled notes (in red pen, as I recall) from Lester Bangs. But my classmate Hank Frank was the first to get a record review–of a Sparks LP, I think it was–published. I was green with envy! By 1971, I was buying Melody Maker and subscribing to the New Musical Express (which came months late, via sea mail, rolled into a baton-like tube). In 12th grade, future TPco-founder Dave Schulps and I would read it furtively behind the large fume-gathering hoods on our desks in an elective chemistry course at Bronx Science that year. I had readHit Parader and 16 Magazine occasionally as a kid. (I recall how the late 16 editrix Gloria Stavers, a fascinating and wonderful woman who we later persuaded to write a Doors article for Trouser Press, would manage to slip names like John Coltrane and Al Jackson Junior into her pages, along with ads, for some instrument company, that pictured Frank Zappa–and you thought it was all the Monkees and Man From U.N.C.L.E.!) Creem was a revelation. Rolling Stone meant nothing to me (unless the Who was on the cover), and continued not to for years–I only got interested when my ambitions as a writer grew to see it as a magazine I’d like to write for. (Which I had.)

The magazines that really led to our thinking about Trouser Press were ZigZag (genealogical history, not an incomprehensible enthusiasm for the wrong kinds of American rock), Crawdaddy (general excellence), Bomp! (record collecting and discographies), Phonograph Record Magazine (serious and entertaining scribing), Alan Betrock’s Rock Marketplace (the mail auction ad business of which we took over when Alan folded it to launch New York Rocker–this was before Goldmine became the ne plus ultra of that realm), Let It Rock and of course the British weeklies.

Dave Schulps and I discovered that the New York Public Library owned a collection of Melody Maker, going back for decades, on microfilm. Dave had this idea of researching British rock using them, so we spent untold hours at the Lincoln Center library, going cross-eyed and seasick as the scratchy old images raced by, writing down every British musician we could find reference to, which bands they had been in, and when. Dave came up with a coding system for instrumentation which I use in note-taking to this day: G/V/K/Y/B/D–guitar, vocals, keyboards, synthesizer, bass, drums–etc. We would write this stuff on sheets of notebook paper, listed vaguely alphabetically, by musician’s name, and attempt to put their careers in chronological order. Then we would go to the stores that sold cutouts and look up the names on records’ back covers to see what we could add to our knowledge base and our record collections.

Dave–who I hasten to add turned me on to the Bonzo Dog Band, Roxy Music, Sparks and a whole of other profoundly formative music–was a fiend for this stuff, and we both learned a lot of bizarre details we would later trot out at interviews and frequently shock subjects with the extent of our knowledge of their careers. (The same idea later became a series of books called Rock Record. But we did it first.)

Steven: If guys like Robert Christgau and Greil Marcus were considered academics and Lester Bangs and Richard Meltzer were considered gonzo writers, would it be fair to say that the stuff you were doing–and your writers at Trouser Press–was more historical stuff. Maybe like Lenny Kaye and Greg Shaw were doing at the time?

Ira: Only at the beginning. As TP went along, especially when the underground scene and new wave started making contemporary music good and exciting again, our emphasis on history faded out. When we started, in 1974, glam was mostly done and there really was a lull in innovation and novelty. So history made us feel like we were doing something valuable–anyway, it was how we learned about music, and we were thirsty for info on what had gone before (in the ’60s, at least. There wasn’t much a whole lot of acknowledged pre-Beatles enthusiasm in our house.) But once things in the music world got good, history started feeling musty and ass-backwards as a journalistic ideal, so we downplayed it. But we never cut it out completely.

At the outset, we were fans who recognized that there was a lot we didn’t know. We weren’t serious record collectors (a joke around our place was to say “The more you pay, the better it sounds” as recognition of how out-of-touch serious collectors could get about music as artifact, not art), but we were devotees of rock history who also loved contemporary music. Lenny Kaye was certainly a hero of mine–his liner notes are responsible for my ever-since obsession with Eddie Cochran–and so was Paul Williams, although I wasn’t as fully aware of his work. Most of the music writers I admired were English–Nik Cohn, Roy Hollingworth (who I buttonholed in a champagne-induced stupor, mine if not his, at a legendary Hawkwind after-show party in NYC in ’73 I think it was), Nick Kent, Pete Frame (who became a pal and contributor to TP), Mick Farren (ditto).

We were completely clueless when we started Trouser Press. There were three people involved–me, Dave and the late Karen Rose, who Dave and I met at a guy’s house in Yonkers. We were into the Who. She was into Jeff Beck. We all knew a couple of people and inveigled them into writing for the magazine. The two cornerstone pieces we got under our belts in the first year were a huge multi-part Yardbirds history by a great guy Karen knew or met called Ben Richardson and a fine Animals retrospective by Dave Fricke, who was still living in Philadelphia and was writing for a local weekly. My dad knew his dad through the stamp business, but we met Fricke through a friend of Dave’s who helped out with Trouser Press in the very early days. I met a Puerto Rican guy who lived on Tiebout Avenue in the Bronx who was into the Beatles and especially their bootlegs.

We did what came naturally, which was to write as exhaustively as we could about the bands and music we loved. Pete Townshend wrote back in reply to the first issue. Lenny Kaye contacted us to say he dug the mag. Dave Marsh looked us up and bought us lunch a year or two in. Kathy Miller, who was a pal of Lester’s and a regular contributor toCreem, as well as a former partner in crime of my first wife, the rock photographer (and NY Dolls fan club co-founder) Linda Danna, wrote some great glam-rock profiles for us.

Dave and I had met Richard Meltzer and Nick Tosches at Susan Blond’s office at UA Records when we were both writing for our respective college papers before we started the magazine in early 1974. We sort of knew Meltzer through Scott Kempner (RM actually wrote an article for Fusion magazine that was supposed to be about the high school band me, Dave, Scott and Hank Frank had that got so far as “rehearsing” in my parents’ living room a couple of times, perfecting a version of “Do You Believe in Magic” that no one else ever heard us play. We thought we were called Gorilla, but Meltzer changed all the relevant details and called us Hank Frank and the Hot Dogs in the article. We were still thrilled.) At UA, where he and Tosches were furiously bagging sealed, un-punched promos they could sell, R.–who remained a personal hero of mine until his insane and juvenile screed about Jon Tiven’s decades-old bathroom activities last year–gave us a crucial bit of advice which I remember to this day. (To be honest, I’m completely paraphrasing, since I probably forget his actual words the next day, that’s how awestruck I was.) He told us to make sure you put something in everything you write that’s just for your own amusement, like ending one word with “s-h” and then starting the next with “i-t.” That beats four years in journalism school (something which I never considered) hands down. Thanks, Dick!

We didn’t have any money (the founding capital budget for TOTP was $60 to buy 10 reams of mimeograph paper, a box of stencils and a couple of tubes of black ink), and we had no idea real rock writers were used to working for nothing. We didn’t know any of the name brand writers personally, and were too shy to meet them. (Dave did get chummy with Gordon Fletcher, a Rolling Stone contributor in DC.) We certainly didn’t imagine they’d be interested in our dinky little enterprise, so we got people we knew, or met, or who found us and volunteered to do writing for the magazine. We kind of knew what we liked, so we knew when we were on to good things. Dave and I both did lots of writing–he emerged as one the magazine’s main feature writers once he finished college and came back to New York in 1975–but we were up for almost anything if it seemed credible and worth reading. Within a year of our starting, Jim Green and Scott Isler had joined the staff; Jim as a singles columnist and feature writer (not to mention distribution manager), and Scott as the art director (and editor in training). Both became major contributors to the magazine over the rest of its life.

Steven: Tell me about your staff at Trouser Press. Did any go on to do bigger things at more mainstream rock mags. For instance, I know Scott Isler went on to do some great stuff at Musician after Trouser Press folded.

Ira: I’ve always been very proud of our alumni and how they spread into various roles in the industry. Jim Green has written for a lot of publications and done liner notes for Rhino as well as build an incipient acting career. Dave, who now lives in L.A., and I work for the same radio company; he’s done plenty of writing over the years for a lot of different publications in the U.S. and U.K. Tim Sommer, who came to work for us a teenaged intern and stayed to become an indie-rock columnist, has already had several brilliant careers, writing for Sounds, newscasting for VH1, rocking in Hugo Largo, signing Hootie and the Blowfish to Atlantic and so on. John Leland, who was also an indie-rock columnist for TP, was on staff at Newsday and Newsweek, the editor of Details and is now a reporter at the New York Times. Jon Young, who was a contributor for many years, has kept up the good work for numerous publications while working in a real job. Steven Grant, another freelance friend of the family, is a big wheel in the comics world. Joel Webber, our first ad director, co-founded the New Music Seminar, put out some very cool records and became an A&R man at Island Records but died in his early 30s of a congenital heart defect. Steve Korté, our second and final ad director, moved on to an editor’s job at Star Hits magazine and has continued to prosper in other publishing realms.

Steven: Did you ever have big time rock writers do any work for Trouser Press?

Ira: Over the life of the magazine, we did publish some big names (Lester Bangs, Pete Frame, Mick Farren, Roy Carr, Gloria Stavers, Chris Salewicz, Dave Marsh), but none of them other than Farren were regular contributors or in any way more than momentarily identified with the magazine. We had some future stars (David Fricke, Kurt Loder, Paul Rambali, Pete Silverton) and some really cool interns (like Fall album cover painter Klaus Castensjold), but by and large we used people we liked. We grew our own.

By the way, although the perception is that women writers were shut out of rock journalism until the post-punk ’80s, we used a lot of women writers, not as a political statement but because they knew their shit and wanted to write for us. Like Creem used to advertise, we didn’t see ourselves as anything special, so we didn’t exclude anybody who could help us. (Plus the magazine was co-founded by a woman.) Toby Goldstein, Marianne Meyer, Karen Schlosberg, MT (Marilyn) Laverty, Kris DeLorenzo, Kathy Miller and Galen Brandt all come immediately to mind, and I’m sure there were others.

Steven: In connection with the above question, I’ve noticed that you never had guys like Marcus or Christgau write for any of your record guides. The writers are always younger, less-known writers. Was that by design because those writers were more in touch with newer, outside the fringe music or did you want to give those younger writers a chance at publishing some of their music writing?

Ira: Yes. I don’t like Marcus’s writing at all, and Christgau has his own record guides to do (for which I have, on one or two occasions, loaned him records), so there’s no chance of either of them being involved in a TP book. On the other hand, Neil Strauss, David Fricke, Karen Schoemer, Gary Graff, Greg Kot, Michael Azerrad, Tom Moon, Jim DeRogatis and many other highly regarded, well-established not-entirely young writers have all contributed.

Basically, I’ve always lived and worked outside the rock critic establishment. I’ve never been friends with any of the big shots (except for Lenny Kaye, and Paul Williams, whom I met in the early ’90s) and I’ve never written for them. Nor most of them for me. I started in rock journalism on the outside and have, for better and worse, remained there for most of my career. I’ve never been in the in crowd.

Steven: What do you think of Bangs and the Gonzo school of rockwrite and Christgau and his more acute approach?

Ira: Nice but not me. I enjoyed reading Lester when I was a kid; thought his Clash trilogy in the NME was brilliant; rarely believed anything he said but often got a laugh out of the superficial silliness; I don’t suppose, in retrospect, I really understood what he was raving about. I re-read a lot of it when his book came out and was struck by how much I had missed hidden in the blizzard of bluster. Meltzer was always more my kind of loony.

Xgau? I have had both fundamental aesthetic and cultural disagreements with his work as well as enormous respect for it. I suspect that the dean has gone through as much of a growth process as have us mere mortals (though his writing has rarely allowed the possibility of incomplete comprehension or knowledge or insight or foresight, so I can’t say for sure whether he would have ever agreed with that assessment), so maybe it’s more a matter of asynchronous timing than outlook. I was never part of his club–maybe that’s why I didn’t get to be the Village Voice‘s music editor the one time I seriously pursued it. Or it could have been because I didn’t really want to work with someone who had once called me a white supremacist in print.

Steven: What do you think of rock journalism today? Do you read any rock mags today and are there any newer writers out there that catch your eye?

Ira: Obviously it’s changed. There’s an astonishing amount of mediocrity in music journalism nowadays–a shocking lack of history and context combined with a congenital audience-pleasing inability to express an independent critical view. I think bad editors have, for good reasons, encouraged a lot of weak writers who have become even worse editors, propagating a downward cycle of incompetence. (That said, the worst editor I have ever worked with was a grizzled old veteran who insisted that everyone should write as incompetently as he did. I tried that for a while but couldn’t hack it and left a very lucrative freelance setup.)

The old values of rock journalism–which, to my mind, are no different than the current values of good journalism in general (like what you see practiced in the New Yorkerunder David Remnick)–have been set aside in favor of a comfortable and profitable collusion between stars, audience and publication. At Trouser Press we always saw ourselves as beholden to no one, and I think that’s largely been lost.

The careerism that emerged once mainstream magazines began covering rock in the ’70s has been a boon and disaster for the field, making it a field one can earn a living in (as opposed to the $10 Creem used to pay, forcing the first wave of writers to live on label largesse and free T-shirts) but encouraging the shallowest of efficient lamebrains who can pitch well and write smoothly but have no original ideas. Considering how many magazines are written largely by freelancers, there’s a major lack of critical depth and strength in a lot of what I read.

Oddly, a lot of the best music journalism is now in daily papers, which once treated pop music like a problem, rather than the music magazines that are devoted to it. I am always happy to read Jon Pareles (by far the finest working critic in America), Greg Kot, Jim DeRogatis, Steve Hochman and Tom Moon, among others. Dave Fricke ofRolling Stone is just as enthusiastic and compelling a writer as he was two decades ago. Tom Sinclair and David Brown both do great work in Entertainment Weekly; I’ve enjoyed Steven Daly’s features in Rolling Stone and Douglas Wolk in the Voice. And while I hasten to note that they are both close friends of mine, I am a big fan of Dave Sprague and Michael Azerrad. I’m sure I’ve forgotten someone blindingly obvious. I’ll think of them later.

Steven: You’ve put out five editions of your comprehensive and intelligent Trouser Press Record Guide. The last edition, The Trouser Press Guide to ’90s Rock, was published in 1997. From what I understand, you are not working on a sixth edition of the book. Are you going through some kind of withdrawal with no book to work on or is the break a welcome one?

Ira: No withdrawal. None whatsoever. And I really can’t see doing another, at least not if I have to edit it. Each edition of the book has been harder to do than the previous one, and while I am a glutton for that sort of self-abuse, at this stage of life I’ve actually come to my senses. The amount of work, stress and concentration they require, editing and writing five of these books has done enormous damage to my personal life and psyche, not to mention my ability to earn a living. And the travails of working with a book publisher presents far more frustration than I can endure any longer. The fifth edition, The Trouser Press Guide to ’90s Rock, wound up taking an entire year, seven days a week, at least 14 hours a day, fighting an impossible self-imposed deadline which I met only to have my publisher waste by bringing it to stores after the big winter buying season, which was the whole point of the deadline in the first place.

Steven: Tell me about what you are doing today. I know you work in radio and your byline crops up from time to time–recently in places like Salon.com and Mojo.

Ira: In the years since Trouser Press ended, I’ve alternately freelanced and worked three real jobs–as an editor at Video Magazine, the pop critic and music editor of (New York) Newsday and, for the past four years, as the editorial director of MJI Broadcasting, a radio syndication company in New York. I oversee a department that provides music and entertainment news to commercial stations all over the country. As you note, I’ve done some pieces for Salon, a Television feature and a Joey Ramone obituary forMojo, some book reviews for the Hartford Courant and assorted other things when the mood has struck. I’ve also written reviews on and off for Rolling Stone, done stuff forEntertainment Weekly and liner notes for a big Rhino project. I know for a lot of people I’ve gone invisible, but I’m still here. Freelance writing for a living is hard–not just financially, but emotionally and ethically–so I do it now for the fun and exercise, writing for people I like who ask me or give me room to write about things I care about.

Steven: Tell me about the future of Trouser Press on-line?

Ira: The site was originally created as a partnership with Sonicnet – I had the “content,” the brand name and the ideas, they had the electronic know-how and resources. It started well but didn’t really go anywhere, and after a series of corporate fish-eating exercises, Sonicnet ended up as part of MTVi, which without any warning or notice near the end of 1999 simply took the site down. They were very nice about giving it back to me, but it took most of a year to get all the registrations transferred etc. So now I have the site back, and have been toying with the next move. There’s the possibility of working with another web site that has expressed interest in a new partnership, or I’ll do it myself. But I’m discovering that to do what I think it should be–all of the contents of the five Trouser Press Record Guides, with some sort of updates for important new releases, plus some archival stuff from old issues of the magazine–is more than I can really do on my own. So I’m kind of mulling and plotting and fiddling with. No timetable. A lot of folks have expressed interest, which is both nice to know and kind of encouraging me to get something done, but I want to do it right, and my available time to devote to it (not to mention web expertise, of which I have very little) is limited.

Steven: Finally, what is your favorite record of all time. If the question is too hard, how about a top five list?

Ira: After 40 years of listening to music as a hobby and a profession, I can’t see any way to select one record as a clear favorite, since each one I love means something different to me, stimulates a different part of my being. It would be more practical to name the musical artists who have meant the most to my life. I guess they would be…

The Who, Bob Dylan, The Beatles, Elvis Costello and the Clash. And Roxy Music, Cheap Trick, the Bonzo Dog Band, Creation, New York Dolls, Ramones, Sex Pistols, Television Personalities, Velvet Underground, Small Faces, Muddy Waters, the Move, Sam Cooke, Eddie Cochran, Bill Monroe, Marvin Gaye, etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc., etc.

I still miss Trouser Press.