I interviewed Wayne a few years back when he was attending an event in Toronto. Spent a very thoughtful two hours in his hotel room, discussing a variety of subjects (cheeseball that I am, I think I even got him to sign a Roxy feature he penned for Creem c. 1974), but for complicated reasons even I can’t recall at this point, I never managed to pull a proper piece together. I still have the audio files, though, perhaps I should, uh, finally get on it.

Category: Creem

America’s Only…

Pop as a Sickness

“People sometimes ask why a serious, well-educated, intellectual fellow such as me wastes his time and enthusiasm on the most insignificant passing trends and the most contrived, trashy music he can find. And I don’t know what to say. I just can’t get into George Harrison, Seals & Crofts or even Van Morrison and the Band. I like that stuff, but it simply doesn’t excite me the way, say, Bobby Sherman or David Peel do. I must be sick.”

– Greg Shaw, review of Slayed, Creem, April 1973

From the Archives: John Kordosh (2004)

The Zen of John Kordosh: Inside the Hallowed Halls of ’80s Creem

By Anthe Rhodes (May 2004)

John Kordosh can blindside anyone with science or pop culture. He was Creem‘s quick-witted everyman who went willingly into those good and not so good nights with the full gamut of musicians. Kordosh, however, has followed a completely different career path than his counterparts. Starting out as a chemist for Dow in his home state of Michigan in the 1970s, he began contributing to Creem in 1980 before joining the staff in ’84 and making the final move to California as a co-editor in ’86. Continue reading “From the Archives: John Kordosh (2004)”

Lester & Philip

That night, after I interviewed Hoffman, I went back to my hotel room and had a dream about Lester, something that happens with some regularity. In every dream, he isn’t dead, but instead has been hiding out somewhere. Waiting. This time, I asked him where he had been. He told me Florida. “I’ve just been waiting for you to get it right,” he told me.

– Remembering Philip Seymour Hoffman, Lester Bangs, and ‘Almost Famous,’ by Jaan Uhelszki (Spin)

Was on vacation (in, oddly enough, Florida), when the news of Philip Seymour Hoffman broke, and of course, my thoughts ran directly to his portrayal of Lester Bangs in Almost Famous (though not only to that; from Boogie Nights onwards, he was terrific in pretty much everything I saw him in). Thanks to Don Allred for pointing me to this excellent piece by Bangs’s old Creem pal, Jaan Uhelszki.

From the Archives: Steven Rosen (2003)

Steven Rosen gets his byline on

By Steven Ward (September 2003)

Veteran rock writer Steven Rosen has been traveling with musicians and profiling them–mostly guitarists–since the early ’70s. He has written for just about every rock publication under the sun. Here, Rosen reflects on five magazines that stand out to him.

Rolling Stone

Maybe the crowning jewel in my literary kingdom. I pitched them a story on Bad Company. This was maybe the first time the magazine printed a story before the album was even released. I received an advance copy of the first album and knew it was going to be a monster. I was right. This was probably a 2,000 word story and I never pored over every comma and colon as much as I did on this one. I was proud of this–it took two years of phone calls ingratiating myself to the editorial staff–pitching them on ideas that constantly got turned down. I believe I dealt with Abe Peck. He was great–guided me through the process, helped me via telephone on re-writes. A story in Rolling Stone–I was cool! Continue reading “From the Archives: Steven Rosen (2003)”

Lou Reed

I’m not embarrassed to say — and hardly alone, I suspect – that my first meaningful encounter with Lou Reed was via Lester Bangs. I had heard of Reed before then, was familiar with “Walk on the Wild Side,” which I thought was just a slightly more offbeat radio song than the dozens of offbeat radio songs then dominating the airwaves (though something or someone eventually clued me in to the fact that there was a Bowie connection, too, and that intrigued me, because I was a total Bowiephile). But I recall the day my brother waved the Bangs vs. Reed Creem Showdown in my face (“Let Us Now Praise Famous Death Dwarves — or How I Slugged it Out with Lou Reed and Stayed Awake”), more or less ordering me, “You have to read this.” Which I did. And which I found exciting and strange. And mostly incomprehensibly intimidating, though I guess I picked up just enough of the gist of the arguments (which were about nothing more than, I don’t know, the future of the human race) that it became an instant touchstone for me, something I would think about (and occasionally attempt to re-read) time and again. I recall in particular being struck by this retort of Lou’s: “You know that I basically like you in spite of myself. Common sense leads me to believe that you’re an idiot, but somehow the epistemological things that you come out with sometimes betray the fact that you’re kind of onomatopoetic in a subterranean reptilian way.” I can’t pinpoint what appealed to me about this; there are at least four words in there I wouldn’t have understood. The sarcasm was quite obvious, and maybe that was the hook for me. Or maybe it’s the poetry of the lines, by which I really just mean their rhythm (you know, they “sound good”). Indeed, I can almost hear Lou talk-singing these very words over one of his more delicate guitar figures.

“You know that I basically like you

in spite of myself.

Common sense leads me to believe

that you’re an idiot,

but somehow

the epistemological things

that you come out with

sometimes betray the fact

that you’re kind of

onomatopoetic

in a subterranean

reptilian way.”

That was my first meaningful Reed encounter, but it was nothing like my last (and thank god for that). Punk took over my life in ’77/’78, and soon enough I figured out that Bangs wasn’t making this shit up, and that Reed and the Velvets were crucial figures — forefathers and all that. Still, I didn’t hear a single note of their music until the fall of 1981, when I bought the first album on a family trip to Boston (one of my two favourite record shopping excursions of all-time; I came home from that same trip with Sandinista!, Entertainment, a four-LP Motown set, and — well, I forget what else right now — the second Specials LP, maybe?). I’ll never forget steeling myself up for my first listen to the Velvet Underground and Nico, preparing to be pulverized by violent, raucous noise, nervous that I would be disappointed or, worse, just not get it. So I drop the needle on side one and receive a much bigger shock than I was prepared for: “Sunday Morning,” a hushed, tender, awesomely beautiful folk-sounding thing that seemed weirdly true to its title. (Believe me, as a wavering though still-obligated Catholic boy, the connection mattered; this was still, if I recall correctly, the era of “the folk mass,” where certain hymns accompanied by strumming acoustics would sometimes induce a lump in the throat.) Of course, it was followed immediately by “Waiting for the Man,” later “Venus in Furs” and “Heroin” (which itself was much prettier than I was expecting) — but “Sunday Morning” was the one that initially stunned. I could not believe this was the Velvet Underground. And I could not have been more thrilled about it. (I know that for many people the first VU album is a massively important 1967 — or anti-’67, as it were — record. And rightly so. For me, however, and for reasons I’ve explained in too much detail elsewhere, it’s got “1981” written all over it. I can’t understand that year, or that era, without turning to the first Velvets album.)

The story doesn’t end there for me, but I’ll end it here for now. There’s going to be (there already is) so much to take in about Reed in the next few days, I imagine it’ll be hard to keep track of it all.

From the Archives: Jaan Uhelszki (2002)

Jaan Uhelszki: Confessions of a Former Subscription Kid

By Scott Woods (April 2002)

As one of Creem‘s senior Editors during the ’70s, Detroit native Jaan Uhelszki was an integral voice during that magazine’s most legendary phase. Uhelszki wrote various columns and dozens of reviews for Creem, though her real forte was the feature profile, in particular her interviews with what used to be disparagingly known as “third generation” rock stars, like Grand Funk Railroad and Kiss. Interestingly, she claims that being a women often aided her in getting the good stories — in part because she wasn’t taken too seriously.

Now based in Berkeley, Uhelszki continues to write for a number of publications, including the British glossy Mojo, as well as Amazon.com.

[Thanks to Jay Blakesberg, who took the photo of Jaan and Joey Ramone.]

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Scott: Please start by telling the readers what exactly you’re up to these days–writing-wise or whatever. Give us a current C.V., please!

Jaan: Unbelievably, I’m still doing exposés and feature stories on rock’s worst offenders. The more socially outcast a band is, the better I like them. I still like to spend time on the road with bands, and decode their lifestyle and psychology (or is that pathology?) for readers. Getting into the minds of musicians has always been fascinating to me. They really aren’t like the rest of us. I review records for Amazon, do features for Mojo, Alternative Press, the San Jose Mercury, and write liner notes for Time-Life and Sony Legacy.

Scott: What were you like in high school? Were you popular? Looking back, would you say your social status then greatly influenced who you are now?

Jaan: I’m not sure my social status determined who I am today, other than the fact that I always looked at myself as an outsider looking in. At the age of 12 I was 5’8″ making me the second tallest person at Lathrup Elementary School. The early height gave me a certain sense of authority, but also set me apart from the 4’11’ more obviously popular kids.

Scott: When and how did you discover rock and roll? Was this something you shared with others, or was it more of a solitary pleasure?

Jaan: I grew up in Detroit, the home of Motown, and because of that, we always seemed to have enlightened radio stations that played amazing stuff. The birth of FM radio, in 1968, opened up an entirely new type of music, in terms of bands like Jimi Hendrix, Cream, Janis Joplin, et. al., as well creating a whole new mysterious subculture that was at odds with the dominant one. When I listened to the radio I felt a part of something bigger than myself–I had joined an exclusive club, where all of us could “hear” Jimi. I think I still can.

Scott: Talk about your evolution as a music critic–was it something you were ambitious to do before joining Creem?

Jaan: I had always wanted to be a music writer. A trip to New York when I was 15 truly opened my eyes, when I first got my hands on a copy of the East Village Other and the Village Voice. They were writing about music in a deep, personal, intimate, intelligent way, and I realized that was exactly what I wanted to do. WhenEye magazine started showing up on news stands when I was in high school it showed me the world of rock celebrity, and I devoured articles by Nik Cohn and Michael Thomas, wishing that I could be doing the same thing. In less than two years I was.

Scott: According to Jim DeRogatis in Let it Blurt, you started at Creem as the “subscription kid”; then Bangs championed your writing and you moved into an editorial position. What was the first piece you wrote for Creem and how did it come about?

Jaan: Actually, Dave Marsh has more to do with my first pieces in Creem than Lester. I think he was sick of hearing me beg to be elevated from the mailroom into the editorial offices. He took me along to a press conference at a swanky Detroit hotel, where Smokey Robinson was announcing his retirement from the Miracles, and promised that I could write about it. I think I thought he was kidding, because I never bothered to take notes or even work up a story. About three weeks later, Marsh called me at home about ten o’clock at night and asked me where my piece was. Chagrined, I told him I hadn’t written it. Marsh actually demanded that I drive the twenty plus miles to the Creem house-cum-offices in Walled Lake, Michigan and pick up some Miracles albums, listen to them, and turn in a full blown story by ten the next morning. Chastened, I actually did what I was told–for once, not even bothering to change out of my night clothes. I buttoned up my blue and white checked bathrobe, fuzzy slippers, sped to the farmhouse, arriving at around eleven that night. I stayed up the entire night hammering out the story, which somehow became anOpen Letter to Smokey, begging him not to retire. Oddly enough that first story was the cover story.

Scott: What exactly were your functions as an Editor at Creem?

Jaan: When I finally worked myself out of my position as the Subscription Kid–three years after I started working there–I was given a battered desk next to Lester Bangs, which was both a blessing and a curse. He could thrash out reviews and features in what seemed liked mere minutes, making me feel like there was something really very wrong with me, since my writing process was much slower than his. I was responsible for creating the news section, “Beat Goes On,” putting together the movie section, after Roberta Cruger left, penning the movie column, “Confessions of a Film Fox,” writing a record review and/or feature a month. Of course, there was the less glamorous work of copy editing and proofreading, and the obligatory staff meetings, where we would all order in ribs and chips and grape pop from Checker Bar-B-Que, and then get into the most awful rows over what was going to be on the cover. As for those famous captions, they were usually a collaborative effort–we all had really skewed senses of humor and played off each other really well.

Scott: Was the staff of Creem in any way aligned against Rolling Stone?

Jaan: It was during that infamous Avis campaign, when the number # 2 car rental company claimed, “We Try Harder” than number #1, Hertz. We felt the same way. We not only believed we tried harder than Rolling Stone, but we were much more irreverent, and as a result more honest. For better or worse, we felt we weren’t beholden to anyone, and made fun of whomever we pleased–often to the detriment of ad sales. We were uncontrollable; the writers at Rolling Stone were very civilized. I think we felt we were much more authentic and rock than they were, and felt a little smug because of it. I guess the smugness made up for big salaries.

Scott: One of the things I most loved about Creem growing up was the lively, usually hilarious letters section. Was there a lot of mail to choose from? Was all of it legit?

Jaan: The letters was always my favorite section, I wish I could tell you that we made them up, but we didn’t have to. I always was amazed how much sicker our readers were than we were. Lester was the letters editor, and he was the one who always wrote the pithy, insulting answers, at least from 1971-76.

Scott: What was the best thing about working at Creem on a daily basis? Also–the worst thing?

Jaan: The best thing was the camaraderie. How great it was to find my own milieu. Everyday wasn’t so much like going to Disneyland, more like living on Donkey Island from Pinocchio–only we looked entirely normal. Sometimes we would make phony phone calls to rock stars whose numbers we happened to come in possession of, or we would speak entirely in the dialogue of “Amos ‘n Andy.” Then there were the days when publicists would bring up-and-coming musicians to our offices. We felt duty bound to play with their minds–just because we could. I’ll never forget the day our publisher Barry Kramer walked into the editorial offices to find Iggy Pop sitting there–and promptly emptied the contents of a trash can over his beautiful, platinum head. Much to his credit, Iggy found no reason to remove it. The worst part was the hours and the demands on our very souls. It was hard work putting out a monthly magazine, special issues, and books, and we tended to work 18-hour days. I usually got into the office at noon, leaving perhaps by 3:00 A.M. on a regular basis. We saw few outsiders, and sometimes it felt like we all belonged to some cult. Having a separate life was almost impossible.

Scott: One thing I always associate in my mind with you is the artist interview/profile. You had a very funny way of bringing the stars down to size. (Let’s just say, you were not exactly Cameron Crowe.) What was the first major pop star interview you did? Describe the experience.

Jaan: I’ve never had any patience with those suck-up, regulation interviews. I figure once you have a rock star in your sights, you’re duty bound to put them on the spot. I grew up reading movie fan magazines, and always wanted to know every single detail about my heroes. I just expanded that philosophy a little, and would query them about the most outrageous aspects of their life I could think of, or ask them the hard questions in a very soft focus way. There’s always something that publicists warn you not to talk about–but I figure if there’s an elephant in the room, you have to acknowledge it, then dissect it. What really surprises me, is how often a star will answer an awkward question. My first interview was a road trip with Steve Miller. I was insanely nervous, but despite his reputation, Miller was really very kind–taking me to dinner at his cousin’s house during one of the tour stops and instructing me in some embarrassing dos and don’ts of on-tour behavior. I remember blushing when he told me writers should never sleep with their interview subjects, because then it would be rather awkward to confront them the next morning with a tape recorder. I always wondered if he said that to the male reporters who toured with him. Ha!

Scott: A piece that you’re very well known for is I Dreamed I Was On Stage With Kiss in my Maidenform Bra. How did this piece come about?

Jaan: I’d always been a fan of George Plimpton’s participatory journalism, and was hugely influenced by Paper Lion, his story about training with the Detroit Lions. That book was really a big deal in Detroit, so I got the idea I should do the same thing with Kiss. Oddly enough, I just called up the publicist and asked if I could perform with them. This was in the relatively early days of Kiss’s career, and they were trying everything to break them–remember the Kissathons in Los Angeles that their label, Casablanca Records, sponsored? Anyway they said yes, and the only promise they extracted was that I wouldn’t call Kiss a “glitter band.” As if I would have!

Scott: Did any members of Kiss respond to the piece afterward?

Jaan: I was the unofficial Kiss editor at Creem, since no one else ever wanted to cover them, so after the piece, I still continued to write about them. None of them thought it was that big a deal. At the time, it was just another story. It just grew in stature as the years went by, probably because no one else has ever performed with them.

Scott: Any particularly disastrous encounters with the rich and famous you care to share?

Jaan: I’ve told this before, but it was my encounter with Jimmy Page from Led Zeppelin. I’d been on the road with them for over a week and couldn’t get him to agree to an interview. Finally on the last day of the tour, he agreed to an audience on the condition that the publicist had to be there. I agreed, but didn’t realize the implication until I began asking my questions. Jimmy stipulated that I must first ask the publicist my question and then she relay the question to him–even though we all spoke the same language, and I was sitting a mere six feet from him. This went on for about an hour, and was so odd, and rather humiliating. Another weird encounter was the time I was on the road with Crosby and Nash, and I didn’t have a room at the hotel, and was forced to bunk on a pool table. That wasn’t as horrible as it seems, but what was worse was they would only do interviews between 3:30-4:30 A.M.. Being on tour with the Allman Brothers was also rather special. Dickie Betts wouldn’t talk to me at all, and then Gregg Allman wouldn’t allow me to use a tape recorder. We would talk, then I would run off to the bathroom every half-hour or so to write everything down he said. It was really disconcerting. Before I left the tour, Gregg gave me a pair of his boots. They were pure white and a men’s size 10. I have rather large feet, but not that large. I never understood the significance of the gift.

Scott: When/how did your position at Creem end?

Jaan: I left in March 1976, for a job in Los Angeles. I was afraid that I was becoming a big fish in a little pond, so I left. Lester left six months after I did.

Scott: What are your thoughts on Creem after Lester Bangs?

Jaan: It’s strange, what has been called the “dream team”–Marsh, Bangs, Ben Edmonds, me, Roberta Cruger, John Morthland–had all left by ’76, so the character of the magazine was very different. We were always fighting with the publisher Barry Kramer about what we should cover and how. He always wanted it more commercial, with more pictures, less copy. After we all left, he more or less had his way. There were some really good writers from the later period, most notably Bill Holdship, Sue Whitall, and Rick Johnson.

Scott: Talk about your relationship with some of the other early Creem cast–Marsh, Barry Kramer, Lisa Robinson, et al. Was it one big happy family?

Jaan: Lisa lived in New York and sent her copy in, but the rest of us lived together in one of two houses paid for by Creem. It was far from a happy family. There were moments of real simpatico, but with such big personalities, there was bound to be sparks. I remember a vicious fight between Lester and Marsh, when Lester’s recalcitrant and untrained dog Muffin defecated on the floor for what seemed liked the thousandth time. For whatever reason, Marsh had had it, and ceremoniously placed the mound of still warm shit on Lester’s typewriter, Lester walked in to see it, then went after David. No one ever seemed to keep anything in. It was always this living theatre. Often staff meetings would disintegrate into fisticuffs–with someone shot-putting a typewriter through a light table, or pitching a telephone through a window.

Scott: Who is your favorite writer of all-time, and why?

Jaan: I’ve always loved Nik Cohn, way before he wrote the magazine piece that became Saturday Night Fever. He was colorful, with a wicked imagination and a really dry, British sensibility, and he never missed a trick. He just had a wonderful way of telling a story, picking out odd little details, which would really define a person. With Nik, God really was in the details.

Scott: Of all the articles, interviews, and reviews that you’ve written, can you single out one that you’re most proud of?

Jaan: My Lynyrd Skynyrd piece for Creem, and the follow-up piece I did for Mojo, 20 years after the plane crash. When I interviewed Ronnie Van Zant for Creemin 1976, he told me that he never thought he’d live to see 30. I pooh-poohed his prophecy, attempting to talk him out of what I though was nonsense. It turned out it wasn’t, and he died in a plane crash in October, 1977. To pay back the debt I felt I owed him, I went to Jacksonville to retrace his life, the crash, and his ghost. It was an amazing, revelatory journey, about the mystery of life itself, and really moved me.

Scott: The part of your rock critic career I’m most familiar with after Creem is the writing you did for Addicted to Noise. How was that experience?

Jaan: It was really brutal work. We were trying to invent a new type of journalism, really. It was like putting out a daily newspaper about music, with a skeleton staff. I was responsible for all the news seven days a week, as well as doing a feature or two a month, transcribing the long-winded interviews–[Editor] Michael Goldbergliked to use every single utterance from a star’s mouth–as well as getting on the phone with managers, publicists, psychics, hotel porters–anyone who had a scrap of rock news. It was invigorating, and I felt so alive doing it. I remember one night my sister, Michael Goldberg, and I were sitting in a Denny’s following R.E.M’s first show after Bill Berry’s aneurysm, writing an account at 2:00 A.M., so we could have it for the next day’s news.

Scott: You did pretty major features on a few of the big Brit-pop acts of the mid-90s. Your Noel Gallagher interview, for instance, was one of the first lengthy pieces I read on them from this side of the Atlantic. Did this just sort of happen, or was it a scene you particularly wanted to cover?

Jaan: I am a total Anglophile. I lived in London for a couple of years, and have a great love for British music. I was a rabid NME reader and had been following their progress up the British charts. When I heard they were coming to San Francisco, I asked for an interview. They were such open, polite innocents then. That is one of the interviews where I couldn’t believe that the interview subject was actually answering my sometimes-intimate questions. It was like Noel was on an English quiz show, and he actually seemed disappointed when I came to the end of my questions. A record company put out that interview on CD; it really is one of my all time favorites.

Scott: Are you able to say what exactly happened with Addicted to Noise? It seemed to be going very strong, and suddenly it wasn’t around anymore. Any inside scoops you can share?

Jaan: When Michael Goldberg sold the company to Sonic Net he lost control. For all his foibles, Goldberg was a true visionary–when he wasn’t at the helm, it floundered.

Scott: What other outlets have you enjoyed writing for? You mentioned something about liner notes, for instance.

Jaan: I love writing liner notes. You’re able to write a historical analysis of something you really care about–and go much deeper than a mere article. I do a lot of stuff for Time-Life and Sony Legacy. I get to revisit many of those acts I covered in the seventies. For instance, Gregg Allman was much more loquacious when I interviewed him for the Best of Gregg Allman, than when I interviewed him in 1974. When I worked on Stevie Ray Vaughan’s box set, I interviewed 30 or so of his friends and famous fans, and it was incredible. I ended up with tears in my eyes during so many of them. Carlos Santana actually wept while talking about him. As for other outlets, I do stuff for Mojo, USA Today, the San Jose Mercury, Alternative Press, Spin, Blender, and Amazon.com.

Scott: Have you done much (or any) writing of a non-rock nature?

Jaan: Yes, I’ve written about politics for a local Berkeley publication, about architecture, photography, food, spiritualism, fashion, and beauty for a number of magazines. I think you can read the culture by what people wear, eat, and believe in, and deconstructing those clues really interests me.

Scott: What are your thoughts on the present state of rock criticism? Are there any writers or publications that you’re particularly impressed with?

Jaan: I think that rock criticism is more restrained. When you write a poor review, or piss off a manager you are denied access. That seems to force writers to play it safe. The publications I like are Blender, Mojo, and In Style (because I’m still invariably nosey about star’s lives).

Scott: What did you think of Phillip Seymour Hoffman’s portrayal of Bangs in Almost Famous?

Jaan: I thought that Hoffman was incredible. He channeled Lester. I interviewed him, and he was eating lunch right through the interview, chewing, talking with food in his mouth and gesturing wildly, just like Lester used to, and I don’t think he was staying in character. He really conveyed Lester’s humanity and kindness, something people often overlooked in him, instead of being captivated by his bombast and the outrageousness of his writing. I think the movie was good, Cameron was forced to create something that would appeal to a large demographic, and while he had to temper the outrageousness of the times for the mainstream, he was able to concoct a truly engaging story.

Scott: Who would you want to play you in The Jaan Uhelszki Story?

Jaan: I guess Bridget Fonda. She has the same birthday that I do.

Scott: What songs would open and close that movie?

Jaan: “1969” by the Stooges and “My Way” by Sid Vicious.

Scott: Along with a handful of other writers–Ellen Willis, Lisa Robinson, and Lillian Roxon first come to mind–you helped break down the barriers of rock criticism to allow some women through the front door. Did this make your job that much more difficult back when you were starting out? Discuss this in relation to editors, as well as publicists and musicians.

Jaan: We lived in the hinterland of Michigan, and I don’t think until I did the Kissette story that anyone knew I was a woman. I was always getting mail addressed to Mr. Jaan Uhelszki; in fact, I still do. I think I had an advantage since there were so few women writers, male rock stars really didn’t take you seriously, believing a female reporter to be a groupie. It seems so silly saying this now, but it happened so often, you’d feel like having cards printed that said: “I’m not a groupie.” But on the upside, you’d tend to get better answers to your questions since the stars didn’t think you’d have the guts to actually be hard-hitting in your stories, so they’d tend to ramble on, and tell you more than they would a male counterpart.

Scott: Did you ever reach a point in your own career where you felt this was a non-issue?

Jaan: There does tend to be an old boy network at some of the established publications, but I think I always thought being a woman writer was a non-issue. I don’t think I haven’t gotten work because I was a woman.

Scott: Although you’d never know it from this site, music criticism is no longer as dominated by men as it was 25 years ago. Do you still feel there are major barriers for a female rock critic to overcome?

Jaan: I think they need to be as fearless as male writers are, and as aggressive in their pursuit of a story. I think woman should form their own network, women helping women. As in life, we’ve never been able to organize successfully enough.

From the Archives: Alan Niester (2002)

Creem’s Canadian Connection:

Interview with Alan Niester

By Andrew Lapointe (April 2002)

Barbeques and weekend trips with Lester Bangs, dangerous encounters on Cass Avenue in Detroit, and the shenanigans of Richard Meltzer: These are just some of the memories rock critic Alan Niester has of Creem magazine.

Niester is a native of Windsor, Ontario, but grew up with his eyes buried in the rock rags from the States, such as Crawdaddy! and Fusion. In the early ’70s, he began freelancing for Creem and Rolling Stone, which meant traveling to the seedy area of Detroit where Creem was located. Alan has some fond and, incidentally, some strange memories of his time at “America’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll Magazine.”

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Andrew: Explain your history as a fan of rock music from early on.

Alan: I guess I got pulled in like so many people did in 1964 with The Beatles on Ed Sullivan. That was actually the first time I got excited about it. Prior to that, I think I bought a few hits compilations, but not as a real fan. I guess I might have been about 13 at the time.

Andrew: How did you start into rock journalism?

Alan: I wrote a little bit in my university newspaper–I actually wrote in my high school newspaper too. I was at the University Of Windsor, writing for the University Of Windsor Lance and buying Creem magazine, although at the time it was in its earliest incarnation, it was kind of a newsprint fold-over. And there was an ad in Creem saying, “Nobody who writes for this rag has anything you don’t have,” encouraging people to send in their reviews and stuff, so I did. I think the first review I sent in was Blodwyn Pig, a Jethro Tull offshoot band. Surprisingly enough, I got a note back, I believe it was from Dave Marsh, saying they liked it and they were going to print it and I should come over and meet them. And at that time, the Creem offices were at Cass Avenue–that would be one of the original Creem offices which were right off downtown Detroit in a pretty seedy neighborhood, and I went over and met Dave and those guys at that time. And I think, as I recall, Lester hadn’t arrived at the magazine at that point. And I just started from there basically. When Dave Marsh quit and went to Rolling Stone as a Record Review Editor, I got some stuff published there as well.

That led to a period of three of four years, maybe 73′ to 77′, where I wasn’t doing too much as I recall–no, maybe the Rolling Stone stuff lasted until about the mid ’70s–and I had moved to Toronto to take up a teaching job. I got a call from the Globe & Mail. The Globe was, at the time, without a music critic, and I can’t remember who the guy was but he just could not write under deadline pressure–writing reviews, he was literally sweating bullets. So they asked me to come on. It was ’77 and I just stayed on, purely as a freelancer for the Globe & Mail, and–I’ve not really done much else. I’ve done a couple things for the Montreal Gazette and a few other things, but as sort of going back to American publications and stuff, I hadn’t really had the time to pursue it. Working for the Globe & Mail and working full time has been more than I can handle.

Andrew: Getting back to Creem, what attracted you to that magazine? Was it the style of the writers or was it something other papers weren’t doing?

Andrew: Did you spend time with the staff?

Alan: Yeah. For the first year or so, it was pretty much a professional type of operation; I think I dealt mostly with Dave. And I really can’t remember exactly at what point I met Lester; I don’t think it was Cass Avenue but it might have been. It might have been when they moved out to the farmhouse in Walled Lake. I can’t remember for sure, but when Lester came on, I started hanging out there a lot more ’cause we had a lot in common. We were both fairly social animals, Lester liked to drink and I liked to drink. We just hit it off pretty well and we started spending a lot of time together. And once Lester was there, then I started spending weekends out at the house on Birmingham and stuff like that. And it was really when Lester came on that I got more involved. But also, I hung out a little with Ben Edmonds, Gary Kenton, and others. Dave wasn’t really a social character; he liked to keep to himself pretty much.

Andrew: Did you ever hang out with Richard Meltzer?

Alan: Yeah, yeah. Richard of course was from New York–then California–so we didn’t see him very often, but there were a couple of memorable times when Richard came and he was quite a character. I remember very specifically a press party, there was this old mansion on the Detroit River called the Gar Wood Mansion, Gar Wood having been a speed boat racer in the 1930s or something, and his mansion sat over the river but the city had taken it over, and Kim Fowley had just recorded an album and was doing a press party, and they actually rented the Gar Wood Mansion for it–it was a big, spooky old place. And I remember Meltzer being there and I think that was the first time I ever met him, and there was a big buffet table for all the press, and Richard actually got up, stood on the table, and urinated into the punch bowl or the shrimp salad or something. That was basically my introduction to Richard; he was a pretty bizarre guy, much more so than Lester. Also, I remember when Nick Kent came from England. The only thing he would eat here was Sara Lee chocolate layer cake, like 3 or 4 times a day.

Andrew: Growing up in Windsor, what was it like to be writing for Creem? You went to the States to spend time with these people; was it kind of surprising and shocking just to be in an different environment outside of Ontario?

Alan: No, not really. Cause by then I was 20 years old or so and I had my own car and if anything I sort of acted like the chauffeur for Lester, ’cause for the longest time he didn’t have his license or he didn’t have his car and I would go out there and it was a little bit freaky when it was on Cass Avenue. I wasn’t there at the time but I remember a story going around that Creem had been visited one day by a bunch of drug lords who had thought drugs were being dealt out of the office, and that it was their territory or something, and that freaked everybody out so much that it precipitated the move out to Birmingham. And it was pretty seedy down there, but once they moved out to the suburbs, it was just getting on the highway and tooling out there.

Andrew: Did you ever feel frightened to be in this seedy area?

Alan: No, not too much. I’m a pretty big guy. It was actually a point where, the drinking age in Windsor was still 21–some of my friends and I would sort of routinely go over to those areas and pick up beer, cause it was the only way we could get it.

Andrew: How did you get from writing for a wild, outrageous rock magazine to a more conservative Canadian newspaper? What was the transition like?

Alan: There was a guy named Bart Testa, and back in those days there were only so many writers and we all sort of knew each other by name and reputation. And Bart–who now teaches at the University Of Toronto, and has for years–was a contributor toCrawdaddy!. And I had at the time a fair number of bylines in Creem and Rolling Stone and some others, and so–I can’t remember whom, but we met at a party or something, somebody thought we would hit it off, and we did. And at that time, he was married to a woman named Ray Mason, who was working as a copy editor at the Globe. I’m not exactly sure why, when theGlobe was looking for another writer or pop critic, they didn’t pursue Bart Testa, who could have done as good or a better job than I could have, but they asked me to do it and I think basically just because of my reputation, because I had some bylines in some of these mags.

I don’t know, the Globe has a reputation for being conservative, but if you look at some of the stuff I’ve done over the years, some of the stuff they would let me get away with was pretty out there. It depends on how you feel on any given day, there’s some concerts and reviews that are so basically boring that it’s hard to write anything edgy about them. It kind of depends on how you feel on any given day and–you could sort of run with it. The Globe has never censored me in any way in terms of if I want to do something a little unusual. So you know, that reputation that they have I don’t think is really deserved.

Andrew: What about writing for Rolling Stone? Did you just send them stuff?

Alan: Yeah, yeah, I mean basically, I wasn’t there for very long and I guess I was kind of their Canadian voice and most of the stuff that I did was Canadian records: the Guess Who, Edward Bear, Lighthouse, and stuff like that. And mostly because Dave Marsh was the editor at the time and I think I managed to hang for a while after Dave left or quit or whatever, and I remember he ended up being the reviews editor for Penthouse, so I can actually say I got some stuff printed in Penthouse too–not something that was actually letters to the editor. I never did anything major for them, it was never anything beyond record reviews.

Andrew: So, you’re teaching now?

Alan: Yeah, I am.

Andrew: Where are you teaching?

Alan: A school in Scarborough.

Andrew: Are you an English teacher, a high school teacher or…?

Alan: Yeah, a high school teacher, English, History, stuff like that.

Andrew: What do the students think of you, as a guy who’s written for rock magazines?

Alan: Students today don’t read newspapers and I manage to keep my two careers fairly separate. A few of them know, but it’s also true that today a lot of the stuff they’re interested in is the stuff I don’t write about anymore. They’re really interested in rap and even some of the heavy metal stuff. I’m still interested in what I write about, but I can’t say I’m really passionate about it anymore. I sort of run hot and cold, but by and large it’s sort of two solitudes, two entirely different lives.

Andrew: What have been some of the best subjects you’ve ever written about? Something you really felt was your best work or something you could remember to this day?

Alan: I guess the most interesting part about the whole thing–and you know, it’s been 25 years at the Globe now–I guess the most interesting thing is that I’ve managed to meet an awful lot of people and interview people live that seems almost incredible to me. I remember talking to Bill Wyman on the phone once and he was sort of rambling on and then half way through the phone conversation he stopped and he said, “Gee, am I talking too much?” And I said, “Well, no.” Here’s an original Rolling Stone, and you’re talking on the phone and he’s asking if he’s talking too much! And Robert Plant chastising me because when he did his album, what was it? Walking Into Clarksdale or something. I said, “What the hell is Clarksdale, anyway?” and he gave me shit ’cause I didn’t know what it was.

Andrew: So, do you enjoy that?

Alan: Yeah I do.

Andrew: I mean, it’s almost stupidly kind of honouring to have a rock star not just talking to you but yelling at you…

Alan: Yeah, yeah. Well, it was good-natured yelling. But I really enjoy that aspect of it. And I have to admit, when I’m talking to people live, I’ll take my album covers down for them to autograph, which is supposed to be a no-no for journalists, but you know, hey, I’m a freelancer, I don’t consider myself a kind of diva in the world of journalism. You know, I’ve got lots of memorabilia on the walls, Eric Clapton magazine covers signed and stuff like that, and that’s kind of, you know, personalized kind of stuff. And I remember interviewing Donovan once, and he’s really out there–the guy’s a real flake–and at the end of the interview, we were in a hotel room, he just picked up his guitar and started playing so I got a personal concert from Donovan. It kind of went on for a while, I remember feeling fairly uncomfortable. But things like that, there have been lots of moments like that that have been really interesting and I think that’s probably been the best aspect of it by and large, because all the people I’ve interviewed over the years, I’ve only had one or two bad experiences. For the most part, the people I’ve talked to have been extremely professional, warm, and friendly. Like Ian Anderson, one of the most interesting people I’ve met in my life–the guy is just fascinating. And James Taylor–extremely warm human being.

Another interesting encounter was with Yes. This happened in the early ’70s, when they were at the height of their powers. I was a big Yes fan–I always loved that British prog-rock stuff. The band at the time was, uh, Squire, Anderson, Howe, maybe Alan White, and Rick Wakeman. I was sent to interview them on the day of a concert at Maple Leaf Gardens. I was amused to discover that the band had not one, but two dressing rooms. One for Squire, Anderson, Howe, and White, which was filled with nuts, berries, white wine, and enough vegetables to stock a small grocery store. The other dressing room was for Wakeman. It was filled with cold cuts and beer. Unlike the other four rather hoity-toity lads, Wakeman was truly Jack the Lad. He was also bored and lonely, and needed a drinking companion. My half-hour interview basically grew into a day-long binge on Wakeman’s rider. Wakeman quit the band soon after. Not exactly a shock. At this point, I’d like to mention that the abuses I wrought on my body three decades ago are no longer part of my lifestyle. I could almost pass myself off as an abstainer these days.

The only bad experiences I’ve ever had with musicians were with The Church, they’re this Australian band–they’re either from Australia or New Zealand–and they were on their first or second record, and they came across as a bunch of complete and utter snobs who could barely condescend to talk to me. I like them, though–I mean, I like their music, and I still get their albums. The only other odd moment I think was with Cab Calloway, the old black entertainer, and I figured I’d just bring my along my tape recorder and press play and he would just ramble on with all of his old stories for a half hour or forty five minutes. The problem was, he was a crotchety old guy, and he didn’t want to talk at all. So basically, there was a lot of dead air, and it was really awkward and uncomfortable. Stuff like that, you know. I remember interviewing Anne Murray once, trying to think if she could remember when I criticized her outfit in one review.

Andrew: Were you familiar with a lot of other Canadians in your field? Like Ritchie Yorke?

Alan: Never met Ritchie Yorke, I know Larry LeBlanc fairly well. Ritchie, I guess, was the generation before I was–not to say he had stopped by the time I was rolling, but I think it was pretty close to that. And of course, my focus originally was with American magazines and I wasn’t living in Toronto so I didn’t get to meet these people. I remember there was a magazine calledBeetle that made its way down to Windsor, I think Ritchie Yorke wrote there, I can’t remember for sure. But no, I had very little contact with the Canadian media at all, there was very little actual Canadian rock writing, and what there was was in the dailies. I eventually met Peter Goddard, but quite after the fact. Now I know most of the guys who write about music or have written about it, and I’ve socialized with Greg Quill and Peter Howell. But back then, most of my focus was on the American writing; that’s where all the writing really was at that point.

Andrew: I think the first review I came across of yours, was of a Guess Who album, it was in Rolling Stone. You said that they were “The Lucille Balls Of Rock.” Do you remember that?

Alan: I cannot vaguely remember it now. It’s a very funny line, I’m glad I said it, but I have no idea what it means at this point. Lester Bangs had a lot of influence on the people who were writing at the time, I was not the only one consciously trying to write in a Lester-esque style. Maybe that’s where it came from, I don’t know. I mean, I was trying to be fairly outrageous at that point, and God knows what it means now. [laughs]

Andrew: So, what are you working on now? Just the teaching and the newspaper?

Alan: Yeah, the stuff with the paper has slowed down a bit, there’s been an editorial change. There are also some ongoing cutbacks at the Globe & Mail, which sort of means they run hot and cold. They obviously have a full-time writer, and I sort of pick up stuff he won’t do, or whatever. You kind of run hot and cold, but that’s fine, I mean, I’m just happy to keep my finger in at this point if I can. I’m not worrying about it too much one way or another.

Andrew: How do you like teaching?

Alan: It’s okay, it’s a living. [laughs]

Andrew: Have you always wanted to be a teacher?

Alan: I just fell into it. I didn’t really know what to do; it’s one of those things where you finish university and–what next? I guess I’ll go teach in college. I remember I was getting sick of university, certainly, and I was offered the job of staying another year and being the editor of the university paper and I mean, I don’t know what would have happened if I had–I guess I would have been a full time journalist. But I really needed to get out of there, I was really sick of it.

Andrew: I just finished Let It Blurt. Did you speak to Jim DeRogatis about the book when he was researching it?

Alan: Yeah, we spoke at length. A lot of stuff that I talked about ended up on the cutting room floor, so to speak. I think I must have talked to him for a good hour or so about the time I knew Lester. Basically, we hung around together a lot from, I don’t know, ’71 or ’72, ’til the time he left Detroit and went to New York. He was a pretty lonely guy in a lot of ways, he didn’t have very much family life, so I would go on Saturdays sometimes. I would take the car and pick him up and bring him back to my family’s house for the weekend. We’d do backyard barbecues with my mom and dad, and he loved it. I mean he would sit in lawn chairs, eating steak and talking politics with the old man, and he seemed to really enjoy that kind of connection. And you know, a lot of driving around, going to bars in the Detroit area and stuff like that. I remember when he finally did get his car, driving out to Ann Arbor, I think, cause he was interviewing John Sinclair of The White Panthers–and I went along with him, and that was pretty exciting. For a 22-year old kid, that was like the heart of the political situation at the time.

But Lester was a bad drunk, a little dangerous. I remember once we were looking for something to do, we were sort of looking for something to eat and we ended up in a White Castle burger joint, half way up Woodward Avenue and we were the only white people in the place, and Lester started “jive talkin'” to the lady behind the counter and the whole place went quiet, and I thought, we’re going to get killed on the spot. I had to pull him out of there. Things like that. There were a number of times I sort of had to basically save his life, because he would just get drunk and do anything and say anything. You know, he’d pass out a lot, so there’d be a lot of schlepping him around and putting him in the back seat of the car to take him home. But, if I were to ever write a Reader’s Digest thing about the most fascinating character I’ve ever met, Lester would certainly be it. Tons of stories. I think I should sit down and write a movie, but I guess Cameron Crowe beat all of us to it.

Andrew: Did you have any contact with Bangs after he left for New York in 1977?

Alan: I think I saw Lester twice after he relocated. My wife and I went to visit him in Lower Manhattan, I think around 1980. [The accompanying photo is from that visit.] Lester didn’t seem to be the Lester of old. He seemed to have lost some of his spunk. He told us that he was in therapy, and he generally didn’t seem too happy. One thing that hadn’t changed, though, were the living conditions. His place was an absolute garbage dump, and the bathroom was so disgusting that my wife was afraid to enter it. If they’d had Fear Factor back then, visiting Lester’s bathroom could have been one of the tasks. Even cockroach eaters would have run screaming!

He also came to Toronto at some point before that. I can’t remember what the occasion was, but I think it may have had something to do with a speaking engagement. I do recall he was granted celebrity status. I think, though I’m not sure, that one of the dailies even interviewed him. Whoever footed the bill also provided the bed, so we were only able to get together on the Saturday night. Of all the places in town to hang out, he chose the Horseshoe Tavern, and we ended up listening to country music while he quite literally cried in his beer. It was kinda like old times.

Andrew: I read about Creem‘s history and it seemed the people at this magazine were just insane and crazy.

Alan: No, I don’t think that’s true. There was a hardcore business sense at work there. Dave was fairly conservative. Barry Kramer and his wife were the owners, and you know, they weren’t party animals and they were kind of distant from me, and their concern was making money, you know. A lot of the people there were fairly professional and they all had a vision of what they wanted to do at the magazine. I mean, Ben Edmonds wasn’t a partyer, per se, Gary Kenton wasn’t a partyer; the only person who was really out there and on the edge was Lester. You know, a lot of the other people were just freelancers like me. We just sort of became part of it, part of the structure of the magazine. They really had a vision, and as interesting as the magazine was…Anything Dave Marsh has been involved in has had a tremendous focus and you know, the pursuit of the rock ‘n’ roll ideology. And Creem was certainly that, they would let people write pretty much what they wanted to write, there were no restrictions on what you could do. I don’t think that was ever the case at Rolling Stone–the editorial hand was a lot heavier. But that is kind of hard for me say, I mean I didn’t do that much for them. The nice thing about Creem is whatever you put down on paper, had a very good chance of getting in the magazine.

Andrew: Even though they were professional, why do you think they were more of an open magazine to all sorts of people?

Alan: Well, the magazine was very unique. I mean, I guess as Lester became more and more involved with the magazine, I think to some degree we started following him, ’cause his writing was fairly extreme and a lot of people simply followed that lead. More than any other magazine out there, Creem believed in rock ‘n’ roll and the rock ‘n’ roll lifestyle and everything that it stood for, and that there should be no restrictions on writing about rock ‘n’ roll, and I think that was the editorial sensibility at the time.

Was Creem a Bastion of Anti-intellectualism? Pt. II

This trashiness was linked to Detroit. In their March 1970 editorial “The Michigan Scene Today,” Barry Kramer, “Deday” LaRene, and Dave Marsh wrote: “It was rock and roll music which first drew us out of our intellectual covens and suburban shells” because “life in Detroit is profoundly anti-intellectual” since its “institutions are industrial and businesslike.” This setting, according to the editorial, gave birth to a youth culture defined not by visions of gentle harmony, but by a more tough-minded, realistic sensibility.

Marsh felt that Detroit was an especially potent site for this powerful force. In Detroit, the music “had to be hard and high energy, too, because the very nature of the city was, and is, dead-set against the Rockicrucian Spirit, and all its implications.” For Marsh, the Motor City “was as anti-metaphysical as the cars that are so aptly its symbol,” but because of this gritty setting, it produced a powerful sensibility that moved between realism and idealism in the search for both countercultural and commercial success

Both quotes taken from Michael J. Kramer’s “Can’t Forget the Motor City” – Creem Magazine, Rock Music, Detroit Identity, Mass Consumerism, and the Counterculture (which was reprinted in rockcritics back in 2003, and will eventually show up back here on the main site as well). I note that Kramer’s piece is cited in Devon Powers’s book, which may be the source of her referring to Creem‘s “anti-intellectual” approach?

Cf. Richard Riegel’s illuminating comment in part 1 of this topic.

Was Creem a Bastion of Anti-intellectualism?

“The writers [Creem] propelled to stardom — Lester Bangs, Dave Marsh, and Nick Tosches being three of the most celebrated — explored rock with a bombast that was smart but anti-intellectual, ‘amateurist and faux lowbrow,’ positioning themselves between the studious class of New York writers and the deference that came out of San Francisco.”

“If Goldstein represented the quandary of what critical practise should be in an age when mediation risked killing the very culture he loved, [early Voice music critic, Annie] Fisher provided an answer: return to pleasure and give up analysis (a stance that would be taken up, in a different way, by the journalists who helped to build Creem)

Both of these quotes are taken from Devon Powers’s Writing the Record: The Village Voice and the Birth of Rock Criticism (pages 6 and 95, respectively). Of the many specious claims I’ve come across in the book (I like some parts of it, too, though on balance I don’t think the author really achieves the enormity of the task at hand), this is the one that most rubbed me the wrong way — i.e., the idea that Creem was this bastion of anti-intellectualism. Also, the idea that the “journalists” at Creem gave up analysis for pleasure (when really, the point, I think, was to not separate pleasure from analysis, to not even recognize a distinction). Labelling what Tosches, Marsh, and Bangs did as “smart but anti-intellectual” in a book entirely devoted to an important strand of the history of rock intellectualism… I just don’t get that at all. Not to say that there probably weren’t some writers in Creem who might have played that as a certain stance, or a certain move. There was always a “this-isn’t-art” argument lurking below the surface of Creem‘s trash aesthetic, not to mention a lot of fucking around, mocking the musicians, etc. I guess I just don’t read that as anti-thought; it was more about expanding how one could think about this stuff, how something could be analyzed in a way that didn’t necessarily scream “analysis” in bold letters. Lester Bangs typing on stage while the J. Geils Band played their set; this was just a different way to do it.

Critical Collage: Rush vs. the Critics

A by no means comprehensive or conclusive survey of a Canadian power trio who once upon a time (much less so now) got under the skins of more rock critics than any other rock or pop artist going.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

“For the record, those three are drummer Neil Peart, who writes all the band’s lyrics and takes fewer solos than might be expected; guitarist Alex Lifeson, whose mile-a-minute buzzing is more numbing than exciting; and bassist, keyboardist and singer Geddy Lee, whose amazingly high-pitched wailing often sounds like Mr. Bill singing heavy metal. If only Mr. Sluggo had been on hand to give these guys a couple good whacks…”

– Steve Pond, review of Rush live in Los Angeles, Rolling Stone, 1980

Geddy Lee’s high-register vocal style has always been a signature of the band – and sometimes a focal point for criticism, especially during the early years of Rush’s career when Lee’s vocals were high-pitched, with a strong likeness to other singers like Robert Plant of Led Zeppelin. A review in the New York Times opined that Lee’s voice ‘suggests a munchkin giving a sermon.’ Although his voice has softened over the years, it is often described as a ‘wail.’ His instrumental abilities, on the other hand, are rarely criticized.

– Wikipedia entry on Rush

– Mark Coleman and Ernesto Lechner, The New Rolling Stone Album Guide, 2004

Nina Hagen vs. Journey

But I hedged my bet right from the beginning too, and kept my day job at the welfare department all the way through, as I was a family man and it provided regular income and medical coverage, etc. That job also gave me another kind of coverage, as a rock critic, as since my writing didn’t furnish my primary income, I could be very choosy who I wrote about. When Creem offered me (among many others) Journey’s management’s junket-to-San-Fran to featureize Steve Perry & co., I could stop believin’ right away and say “NO!” It was fine with me if Journey got written up in Creem, but I didn’t want my byline on the piece. I reserved that for say, a $5. Rock-a-Rama (capsule review) of Nina Hagen, one of my heroine-addictions of the time.

– Richard Riegel, Where Did (My) Zeitgeist Go?

I’d never seen this piece before (it’s from the blogger’s section of Rock’s Backpages) — rockcritics‘ fave rave, Richard Riegel, just having devoured Chuck Eddy’s latest critical tome, reflects on his own career/half-career in music criticism.

Disco Bubblegum

“There are many substantial reasons for linking disco with bubblegum; the comparisons, endless. Like [Kasenetz and Katz]‘s clapping sound, Euro- and pop-disco are essentially mediums for a producer’s special sound, whereas the performer’s role remains secondary. Disco combines a constant beat with simple lyrics; like bubblegum’s skip-a-rope dynamics, its function is strictly to provide rhythms for people entangles in the exercise of dance. Furthermore, many disco bands are merely media-crafted vehicles for a producer’s concept. Aren’t Jacques Morali’s Village People just a chic model of K-K’s 1910 Fruitgum Co.?”

– Robot A. Hull, “Yummy, Yummy, Chewy Chewy: A Bubblegum Yarn,” Creem, October 1979

Creem Magazine Review (YouTube)

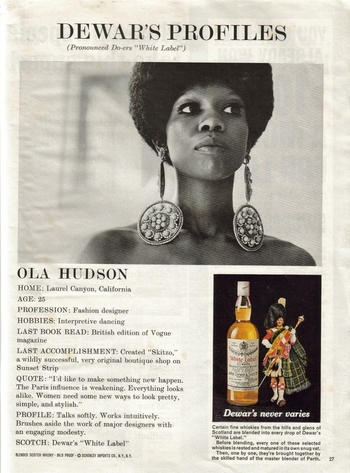

Less a review, than a tribute, but not bad (there’s no info I can see about who made the thing). There are a couple minor factual quibbles, and it’s a little odd that he quotes stuff from Christgau and Marsh that have no connection to Creem. But a couple lines in it made me laugh (“these were some dead honest, music-lovin’ motherfuckers”), and I learned something new (something I probably should have known but didn’t): the Creem Profiles section was actually a pisstake on Dewar’s scotch.

Carola Dibbell on Fiction and Music Writing

An interview with Carola Dibbell at Black Clock:

BLACK CLOCK: You wrote rock criticism on and off for thirty years and have spoken before about the leakage between fiction and music writing. Can you explain what you mean by that? What role has music played in your fiction?

CAROLA DIBBELL: In the early seventies, I was surprised and impressed by the rock writing in Dave Marsh’s and Lester Bangs’ Creem, and a little later in the Village Voice music section, edited by Robert Christgau, my husband. In this fledgling and disreputable form, you could be vulgar, personal, amateurish and formally ambitious all at once and actually be read. It gave me a chance to do things with the voice and tone and disorder I was already exploring in fiction that was not actually read. It took longer for me to bring those rock critic elements into my fiction except, I suppose, that writing about pop led me to contemplate genre fiction. Then, in the late nineties, when my fiction was going nowhere, I made a conscious decision to let the rock critic write the fiction, sort of, and the fiction changed a lot.